I have just finished publishing my book, Evidence Considered: A Response to Evidence for God. I wanted to put a few notes down about the technical side of this process: what got me into it, what software I used, and the surprising story of obtaining permissions.

History or Why I Started Writing and What Kept Me Going

I wrote this book accidentally, only realizing half way through that it might be worth converting my blog series into a book. The blog series was a set of posts responding to a collection of essays entitled Evidence for God: 50 Arguments for Faith from the Bible, History, Philosophy, and Science. But I realized that my argument for atheism is the same as a set of reasons for why theistic arguments fail to persuade me. And 50 arguments would surely cover many of the main reasons people have for belief.

Of course, it does not cover all of them. How could it? And one has to trade off breadth for depth. So other arguments and deeper considerations will have to wait for later books.

But what made me excited about this project was the realization that a closer examination of the arguments for God often reveals arguments for the human origins of faith.

I had thought my blog was reasonably well polished. I had not appreciated (though I knew in theory) how much work goes into polishing. After about twenty drafts, I can tell you that going from nothing to the first draft is far less work going from the first draft to the final copy.

You have probably heard this in various maxims: you don’t write a book; you rewrite it. Or don’t write it right, write it down. Or get the bad writing out. I had sort of been hoping that it did not apply to me because my writing was so wonderful. Oh boy, was that a lesson in humility.

The other thing that caught me off guard was that I was no less prone to cutting remarks, barbed comments, assuming bad intentions, and general lack of respect than many of those I criticize for the same thing. After fifteen edits I was still finding sentences that served no other purpose and could be redacted without any loss. This is especially odd since I was writing to my former self!

I am particularly indebted to my friend Adam Clulow for his honest and insightful comments to this effect. I had, funnily enough, been removing that kind of tone from the book for several edits, but he really nailed it in his feedback. I read his comments several times and after a period of denial realized that he was correct and that I would have to go through the whole book again. Again.

But in many ways, this has become the central thesis of the book: how can we have this hugely important discussion respectfully and honestly and, in the end, agree to disagree. But really agree to disagree. Without assuming bad intent, poor knowledge, or faulty logic. Just a different perspective. Changing my mind on my religious beliefs was another lesson in humility. Our beliefs shape our lives and our societies, so we need to talk about it.

One of the ways these barbed comments sneak in is that when you write the first draft you are sitting in front of a blank screen, your fingers poised over the keyboard, thinking about what to say. It is like an awkward pause in a conversation, and so you fill it in with the first thing that comes to mind. This is often just a reflection of the aggression you perceive is coming from someone who is disagreeing with you. At the time, they were some of my favorite sentences. But in later editing, they simply have to be cut. I came to see the entire conversation in a very different way.

My book is not particularly aiming to convince people (apart from indirectly through the Socratic method). It is trying to show why I am not persuaded by certain arguments. My conceit, if you could call it that, is that I will not pretend to be convinced when I am not.

Writing an eBook

On the writing side, I started on Tumblr but moved across to an open source epub editor called Sigil. I also moved my blog across to WordPress. Epub is an HTML like language, and Sigil gives you both the WYSIWYG (“What you see is what you get”) and the markdown interfaces. Knowing that I wanted to write an eBook, at least initially, made this a relatively easy decision. Especially since I wanted linked footnotes.

One of the advanced features of Sigil is the regular expression search. You will find much pain expressed about these by anyone who has tried them. I did have an exciting moment when I did something foolish that wrecked havoc on my manuscript and cost me a morning. With great power comes great responsibility! But it was incredibly useful in some circumstances.

For example, I often quote from the original book (Evidence for God), and when I do so, often change the tense of the first letter as follows: “[T]his is an example.”

This formatting did not play nicely with the spell check. With regular expressions in Sigil, it is possible to change them all to something like “*** This is an example,” perform the spell check and then change them all back again. One could, in theory, do that with 52 finds and replaces, and revert with another 52 find and replaces, but regular expressions allow you to do it in one step each way.

I also, at some point, needed to find all the Bible references in the book (more about this below), which could also be done with regular expressions.

I wrote the whole book in Sigil and found the software was good enough to read it through several times, making edits as I went. One of the issues with making edits is that towards the end of a long day when your eyes are starting to see double, some of your fixes create more errors. As a slightly obsessive person, I found I needed to force myself to take a break and go for a run or to the climbing gym to mitigate this.

Eventually, I used Calibre to convert the book to PDF and to Mobi, the native format for my beloved Kindle. The PDF was used to print the whole book and do markups on the paper. Many thanks also to my lovely wife for going through the entire manuscript and marking it up early on.

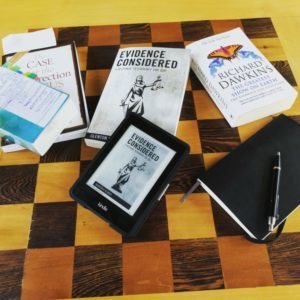

I also put it on my Kindle and read it there, keeping track of my ideas for edits in my trusty Moleskine notebook. Changing formats and not being able to edit while reading was definitely worth it for the later edits.

One of the mental obstacles is shifting mode from editing to writing. You can be sitting reading, and perhaps making the odd tweak here and there and then happen upon something that is wrong. One has to fight through the grief, negotiating, and denial before acceptance comes and you dig in.

Worse still, there were times I had to go back to research mode. Of course, I love reading and learning and it is a privilege of writing that you can do so. But the transition from editing with the happy dream of finishing the chapter in the next hour or two suddenly becoming a week or two can be demoralizing.

Creating a Paperback

After the eBook, I wanted to do the paperback version. Amazon’s KDP makes this relatively easy, but again I rapidly discovered my naïveté. I had thought that I would save a separate version, delete a bunch of the endnotes that were only appropriate for an eBook where space was not a concern, and be done! But, of course, eBook and paperback are very different kettles of fish.

The eBook format is designed to be flexible, adjusting automatically to different reading circumstances and devices. The endnotes are links and page numbers are meaningless.

A paperback is designed to be fixed. Every pixel is there for a reason. I went for a run and realized that I would need to put the whole thing into a different program designed for typesetting. LaTeX is such a program, and happily, it is in common usage in the science community and so I had some (slightly dusty) experience with it. KDP requires a cover and a layout, preferring PDF, and PDF is a strength of LaTeX.

I was able to use a Python script to go through my epub (the native eBook format of Sigil) and pull out the text files necessary to go into LaTeX. I was also able to go use this same Python script to find instances of epub mark up and convert them to the corresponding LaTeX version. For instance, the epub markup of:

<h2>Chapter 1: The Cosmological Argument</h2>

needed to be changed to the LaTeX markup of:

\chapter{Chapter 1: The Cosmological Argument}

With Python that is easy enough, and I was able to change all instances of such things automatically. This was a huge time-saver and, as with all automation, increased the quality and consistency.

LaTeX is a program that feeds on Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (or CDO as a friend of mine calls hers since she prefers the letters in alphabetical order). I found myself waking at 4 a.m. and wondering down to work on it. I had nightmares of people pointing out that half the chapters were missing from the finished work (I checked. They’re all there. Hang on, let me check again). But after three days of this, I had a PDF with which I was happy. The cover too needed just a little tweaking to get the size correct (Thanks, again, Josh), and to use a higher resolution image from that used on Kindle.

The biggest change was a shift from endnotes to footnotes. In particular, in the eBook version, I include a large number of Bible verses, to make it easy for the reader. I needed to remove most of these, leaving instead just the reference so the reader could look it up.

Secondly, the eBook has links back and forth, so that each chapter can stand alone and the reader can jump to other chapters that are relevant. Obviously, a paperback cannot have links, but LaTeX makes it possible to add “on the next page” or “on page xxx” in places where that is useful. It is particularly important to have a computer do this. The idea of doing this kind of thing manually brings me out in a cold sweat. Even trying to automate this on something like Word is inadequate. For example, you want it to be able to automatically detect when it’s on an adjacent page and say something sensible like “on the previous page” or “on page xxx” if it’s further away. LaTeX has a package that handles this all automatically and very cleanly, even varying the wording a little so that it is not monotonous.

And finally, the formatting associated with parts, chapters, front matter, headers, page numbering and so forth had to be decided and tweaked in some cases. With an eBook, you essentially say that you are starting a chapter and allow the formatting to be done by the device. With a paperback, it is all aesthetic choices. And on the internet, you can find people who are very passionate about what those choices exactly are and why.

One of the neat things about KDP (and CreateSpace) is that there’s no money down. Once you get the book setup the way you like it, you can put it up and start selling it. Amazon just prints it out on demand. I’m selling the eBook for $1.99 and the paperback for $9.99 currently, and am getting about $0.70 per copy either way. Half of which will go to the tax man, I guess.

It was an incredible thrill to hold my book in my hands.

Permissions and Quoting from the Bible

My book quotes heavily from Evidence for God to try to summarize the argument before explaining why it does not satisfy me. It seems that one of the criteria for “fair use” is if you are taking up a contrary position. However, it’s always safer to ask, and so I received permission from the publisher of Evidence for God. The process was relatively painless. Similar to other books from which I quoted. The permissions departments typically got back to me within days and were easy to work with.

One of the areas that caught me off guard was quoting from the Bible. In the eBook version, in particular, I wanted to include most of the Bible references I use in the endnotes so that the reader can see the context easily at their fingertips. And I wanted that for at least some of the verses in the paperback version. I commonly use the NIV, and so I used that, with the expectation that it would be a formality to receive permission to use it, if necessary at all. Their website stated that up to 500 verses could be used without permission. “Verses” not “references” which made it a little marginal, since I sometimes quoted larger sections to establish a bit of context.

On May 8, 2017, I wrote to them as follows:

Attached please find a permissions request form for NIV scripture quotes to be included in a book I am writing. It is very marginal whether I need permission, as I may have less than 500 verses, but I did not want to take a risk. Since I am publishing the book as an ebook, I have included many of the scripture references in the endnotes for the reader’s convenience, which is the vast majority of the references in the book.

On May 31, 2017, they responded:

Thank you for your request and interest in the ministry of Biblica. Will you send me a list of scriptures you will be using in your Work.

I look forward to hearing back from you soon.

Like that’s no big deal. Generally, extracting a list of verses quotes in a 100,000-word manuscript would be a pretty big job. I guess it’s a fair request. Thankfully, I know a bit of Python and enjoy the coding challenge, so the next day I responded with the list. I also mentioned that I could give them the list in a different format or show which ones are used in which chapter or whatever.

A month later (Aug 1) I receive an email saying:

Thank you for your request. Will you send me the title of your book?

Funnily enough, this information is not in the request form that I downloaded from their website, so I wrote back letting them know. They responded (Aug 2) with:

Thank you for your request. Below is a link to your letter of permission. If you are in agreement with the terms therein, please print and sign 2 copies, and return one to me for our records.

The permission was for only two years, only 1,000 copies, and only within North America. I was not about to accept such restrictions on my book, especially not for quoting from the Bible.

Of course, there are versions that are out of copyright, notably the King James. But the King James has old fashioned language, which I personally find distracting, even if it is the version that is commonly in the public consciousness.

More searching led me to the World English Bible, deliberately named to have the acronym WEB. It is based on the King James (indirectly: it is an update of the American Standard Version of 1901), so it feels familiar, but has been put into contemporary vernacular. And has been specifically placed into the Public Domain, so that it is free to use. In fact, it is currently the only English version that is a complete, public domain, contemporary language version.

The Open English Bible is working towards this goal, but has not got there yet. It is more NIV-like in translation. That is, it is based on the Westcott & Hort critical text rather than the Tyndale tradition. People have very strong opinions about this on all sides, needless to say!

This is what John 3:16 says in various versions:

- KJV: For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.

- NKJV: For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have everlasting life.

- ASV: For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth on him should not perish, but have eternal life.

- WEB: For God so loved the world, that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish, but have eternal life.

- NIV: For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.

- OEB: For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not be lost, but have eternal life.

Funnily enough, it is almost verbatim with the NIV in this instance. Okay, let me show you a different verse. Romans 6:23:

- KJV: For the wages of sin is death; but the gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord.

- NKJV: For the wages of sin is death; but the gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord.

- ASV: For the wages of sin is death; but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.

- WEB: For the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.

- NIV: For the wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.

- OEB: The wages of sin are death, but the gift of God is eternal life, through union with Christ Jesus, our Lord.

It starts to look like the vanity of small differences. But here the common heritage with the ASV is clear.

Anyway, I wrote back to the NIV people and told them not to worry, and then spent a couple of days shifting my verses across to the WEB version (again, regular expression seaching made this far easier). Having the NIV there before I copied the WEB across was handy, as I was able to do a side-by-side comparison. It rarely made a difference to the point I was making, though there were a couple of small differences that were notable.

More than a Year Later…

So now the book is available on Amazon. It’s been more than a year since I started, but I’ve really enjoyed the process. The learning, reading, weighing, discussing, writing, and obsessing have been both cathartic and informative. And more than that, it’s been an excuse to talk to people about their beliefs. Just that has made it all worthwhile. We have a cultural taboo against talking about why we believe what we do, and writing a book breaks down this barrier. It is something that unlocks an extraordinary wealth of conversation. And it is a conversation that almost everyone wants to have, at least after the initial awkwardness.

I hope everyone will start asking “what do you believe and why?” Done with respect and curiosity it has led to some of the most fascinating conversations I have had.